OAST; Gleam

It going tobe a long travel day back to the Maine compound, so we’ll stay theme-less and tap into just two topics (since they are long-ish) that were near the top of the share pile.

TL;DR

(This is an LLM/GPT-generated summary of today’s Drop. It’s Ollama and MiniMax M2.1 since it just got released.)

- The author investigated OAST (Out Of Band Security Testing) techniques after noticing an initial access broker campaign, discovering how attackers use external callback domains to detect blind vulnerabilities and identifying tools like ProjectDiscovery’s Interactsh and structured domain encoding methods (https://www.labs.greynoise.io//grimoire/2025-12-26-coldfusion/)

- Gleam is a statically-typed language that compiles to both Erlang and JavaScript, combining BEAM virtual machine reliability with modern syntax and world-class error messages, making it ideal for web developers seeking type-safety without the complexity of Rust (https://gleam.run/)

OAST

Despite $WORK being on a forced Winter break, I have a difficult time not checking in with what nefarious things are happening on the internet. Late last week I noticed some shenanigans going on that forced me to re-enter the world of Out Of Band Security Testing, or “OAST” for short (b/c we cyber folks love acronyms more than life itself). While I’ve known about these domains since their inception, they are primarily used by bug-bounty hunters, and I think I’ve made my position pretty clear on the utility/efficacy of that particular side of cyber.

Traditional security tools often operate like a one-way conversation: the scanner sends a “fake attack,” and if the website responds with a specific error or behavior, a vulnerability is flagged. However, this creates a significant blind spot. Some of the most dangerous vulnerabilities are “blind,” meaning the attack successfully compromises the system, but the website remains silent, never sending a response back to the scanner. This makes these critical flaws completely invisible to standard security tools.

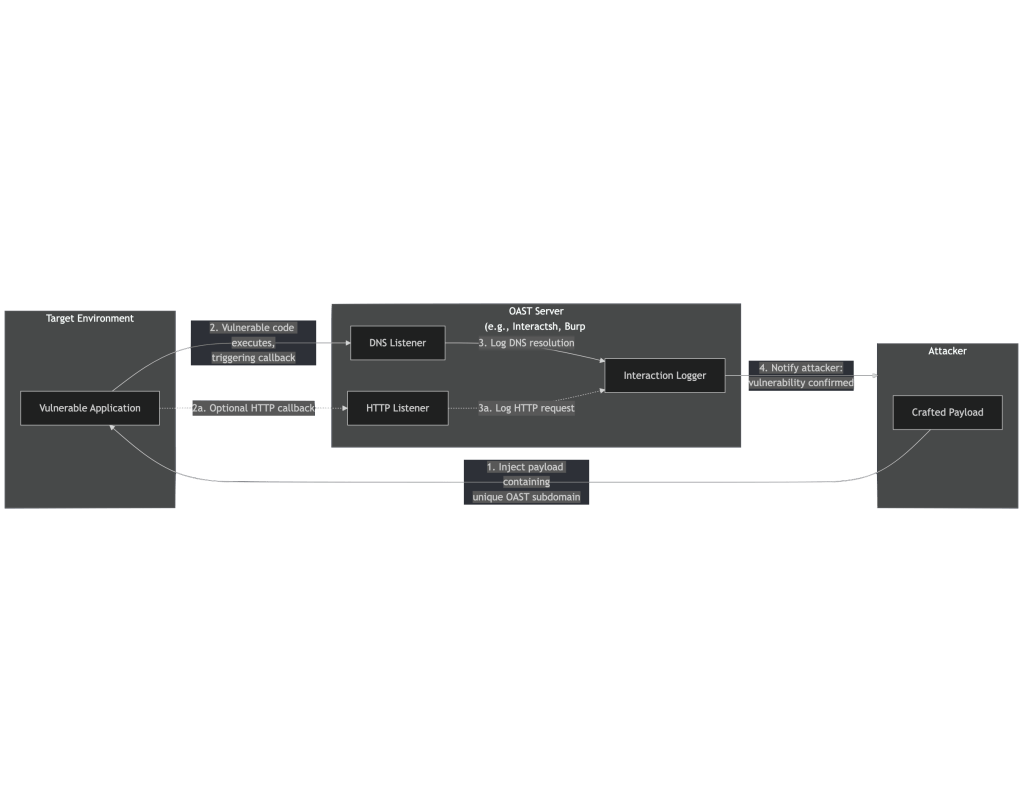

To solve this, OAST introduces an “intermediary” strategy using an external server. Instead of waiting for a direct reply, the scanner sends a specialized payload that instructs the website to reach out to a third-party server if the exploit is successful. When that external server receives a “ping,” it provides definitive proof of a vulnerability. This allows security teams to “see around corners” and detect hidden threats that would otherwise go unnoticed. It also, in the case of the initial access broker campaign in the GN Labs’ blog I linked to, lets attackers build an inventory of vulnerable systems.

The section header’s diagram attempts to show the OAST flow. ZAProxy’s docs have more OAST info and better diagrams.

One of the most popular tools/services for working with OAST is ProjectDiscovery’s Interactsh. While Interactsh is designed to help cybersecurity professionals, the initial access broker also used it and a slew of ProjectDiscovery’s Nuclei Templates to identify pretty much every vulnerable server on the internet.

We track many of OAST callback domains at $WORK:

interact.[com|sh]oast.[pro|live|site|online|fun|me]burpcollaborator.netoastify.comcanarytokens.comrequestbin.netdnslog.cnpastebin.comceye.io

and regularly add new ones as they pop up.

This is an example OAST callback subdomain (from the IAB campaign) using oast.pro’s TLD:

d57kdi03t4ggk08h8a1gy9h3pcjja3d3i.oast.pro

You should stronly consider not letting any system in your organization resolve anything under those top-level domains (TLDs), but it’s so easy for an attacker to host their own callback domain that you’ll be playing whack-a-mole if you try to extend that particular defense beyone popular lists.

As Sandia Labs’ John Jarocki’s demonstrates in his epic LabsCon presentation, some of these OAST systems use algorithmically-generated and highly structured identifiers, which we can decode:

c58bduhe008dovpvhvugcfemp9yyyyyyn.oast.pro

|------ preamble -----||- nonce -|

The first 20 characters are base32hex-encoded (RFC 4648) representing a 12-byte XID:

- Base32hex alphabet:

0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuv - Encoding: 20 chars × 5 bits = 100 bits → 12 bytes (96 bits used, 4 bits discarded)

Field Layout (12 bytes):

| Bytes | Field | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-3 | Timestamp | uint32 (big-endian) | Unix timestamp (seconds since epoch) |

| 4-6 | Machine ID | 3 bytes | First 3 bytes of hashed platform UUID |

| 7-8 | PID | uint16 (big-endian) | Process ID |

| 9-11 | Counter | 24-bit (big-endian) | Incremental counter (random start) |

Derived Fields:

- K-Sort: First 6 characters of preamble (timestamp-based, K-sortable)

- Campaign: Characters 7-11 of preamble (campaign identifier for grouping)

- Nonce: Characters 21+ using z-base-32 alphabet (session uniqueness)

The decoded version of the example domain (above) looks like this:

{

"original": "d57kdi03t4ggk08h8a1gy9h3pcjja3d3i.oast.pro",

"timestamp": "2025-12-26T21:39:04-05:00",

"machine_id": "03:e9:21",

"pid": 2561,

"counter": 1131139,

"nonce": "y9h3pcjja3d3i",

"ksort": "d57kdi",

"campaign": "03t4g",

"valid": true

}

Since I had to process tens-of-thousands of unique OAST domains for that campaign, I wrote a C-backed R package along with a pretty robust Golang OAST Domain Library + CLI + MCP Server that makes it straightforward to glean lots of useful info about the more structured addresses. The aforelinked Labs’ blog has details from said extraction and analysis.

Seeing these domains used at-scale in a highly-professional IAB attacker campaign has given me a newfound appreciation for this slice of cyber, and we’ll likely be adding more OAST-usage details to our platform in 2026.

Gleam

Throughout 2025 I’ve had a bit of FOMO regarding Gleam (GH), a _“friendly language for building type-safe, scalable systems.” In the most simple terms, Gleam combines the bulletproof reliability of old-school telecom systems with a modern, easy-to-read style. I haven’t had the time to play much with new languages this year, and since lots of folks are doing some interesting projects with Gleam, I decided to poke at it a bit over the break after #2.1 and #2.2’s bedtimes.

To understand Gleam, one has to know about the BEAM virtual machine that powers it. The BEAM was originally built by Ericsson to run global phone networks, so it’s designed to handle millions of things happening at once and to essentially never crash. While there are other languages on the BEAM (e.g., Elixir or Erlang), they generally are dynamic (i.e., they figure things out as they run). Gleam, however, is statically typed. This means the compiler acts like a super-smart proofreader, catching mistakes before code is ever run.

Right off the bat, there were a few quality-of-life features that make Gleam very interesting. First, there’s the “if it compiles, it works” factor. Gleam’s type system is robust enough to eliminate entire categories of bugs (like null pointer errors) before you deploy any project. The tooling is also blazingly fast since the compiler, formatter, and package manager are all written in Rust, often compiling an entire project in the blink of an eye. Then there’s the pipe operator (|>), which makes code read like a clear recipe instead of nesting functions inside each other like an onion. And perhaps most compelling for 2025: Gleam can compile to both Erlang and JavaScript, meaning you can write your backend and frontend code in the same language while sharing data structures perfectly between them.

The syntax itself looks like a clean mix of Rust, Swift, and Go with no magic or hidden behaviors:

import gleam/io

pub fn main() {

let greeting = "Hello"

let name = "Gleamlin"

// The Pipe Operator in action

name

|> create_message(greeting)

|> io.println

}

fn create_message(name: String, greeting: String) -> String {

greeting <> ", " <> name <> "!"

}

So, after said poking it appears Gleam is aimed squarely at web developers (since it compiles to JS) who want Elixir’s reliability but miss TypeScript or Rust’s type-safety. (Yes, I know “TypeScript” exists to do something similar, but it has the stench of Microsoft on it, which I cannot abide for much longer.)

It also seems tailor made for the “productive” coder who finds Rust too complex (all that borrow checker wrestling) and other languages too loose. And if you’re on a team that hates debugging, you’ll appreciate that Gleam’s error messages are genuinely world-class. They don’t just tell you something is wrong; they politely explain why and suggest how to fix it.

On the news front, Gleam v1.14 dropped in December 2025 as a “Happy Holidays” release, introducing External Annotations. This makes it much easier for Gleam to talk to other languages like TypeScript or Erlang, ensuring that when you’re using a library written in a different language, the types stay perfectly in sync.

Going into the specifics of Gleam is not something we can tackle in a Drop, and both of these resources do a phenom job helping you grok it and the broader Gleam ecosystem:

While we won’t get into the weeds, this is how I installed and checked out the boilerplate/default initial Gleam project:

➜ mise use gleam@latest

➜ gleam new first

Your Gleam project first has been successfully created.

The project can be compiled and tested by running these commands:

cd first

gleam test

➜ tree --du -h first

[1.7K] first

├── [ 542] gleam.toml

├── [ 463] README.md

├── [ 172] src

│ └── [ 76] first.gleam

└── [ 326] test

└── [ 230] first_test.gleam

1.8K used in 3 directories, 4 files

➜ cd first

➜ gleam run

Resolving versions

Downloading packages

Downloaded 2 packages in 0.03s

Added gleam_stdlib v0.67.1

Added gleeunit v1.9.0

Compiling gleam_stdlib

Compiling gleeunit

Compiling first

Compiled in 0.47s

Running first.main

Hello from first!

➜ tree --du -h first

# FULL OUTPUT AT https://codeberg.org/hrbrmstr/gists/src/branch/main/2025/2025-12-29-gleam.md

10M used in 30 directories, 249 files

I did that last bit in the code block to show it’s like Go/Rust/JS/etc. which vendors in a bunch of dependencies.

Zed has a decent Gleam extension, which I’ve started to put through some paces by attempting to port the Golang OAST code to Gleam. It will definitely be slow going, but I’ll report back in a future Drop on how it went.

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

☮️

Leave a comment