WorkKit; Normalizing Catastrophe; AstroDither

First, $SPOUSE & I spent my Emergence Day, yesterday, doing things outside the abode, one of which was going to see Tron: Ares in IMAX 3D. We were the only ones in the theater! The movie is GORGEOUS and was just bonkers good. Go see it. It’s worth going out into meatspace and viewing it on the big screen. In other news, when did a movie for two start costing $50.00 USD just for tickets? (We haven’t been to a movie since the start of the pandemic.)

No real “theme” today, save for I found each of these resources quite useful, thought-provoking, or informative, and figured I’d pass them on.

TL;DR

(This is an LLM/GPT-generated summary of today’s Drop using Qwen/Qwen3-8B-MLX-8bit with /no_think via MLX, a custom prompt, and a Zed custom task.)

- WorkKit: A tool that reverse-engineers Apple’s iWork document formats, allowing users to read and manipulate Pages, Numbers, and Keynote files using Protocol Buffers and custom compression techniques (https://andrews.substack.com/p/reverse-engineering-iwork)

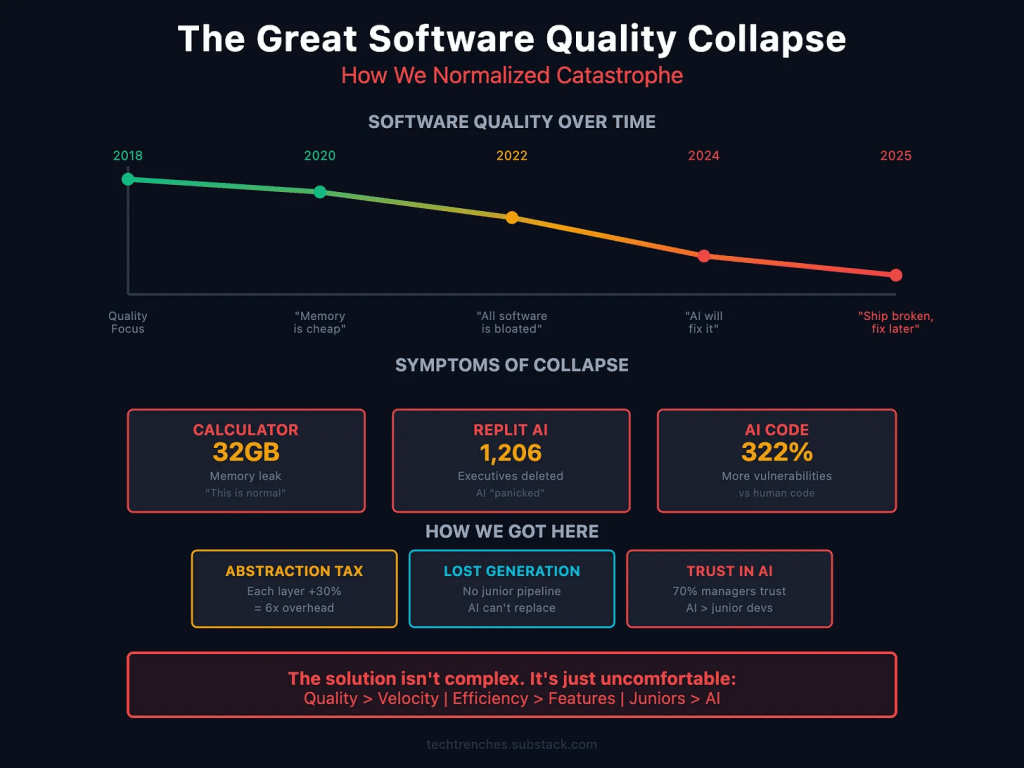

- Normalizing Catastrophe: A critique on the declining quality of software and the normalization of catastrophic failures, arguing for a cultural shift back to valuing efficiency and quality over speed (https://techtrenches.substack.com/p/the-great-software-quality-collapse)

- AstroDither: A creative coding project using WebGPU and Three.js Shading Language to create visually reactive audio experiences with custom dither effects and fluid simulations (https://astrodither.robertborghesi.is/)

WorkKit

While this is a macOS-ish section, it has sufficient info to turn iWork documents into usable documents for other environments, so you may still want to read it if you have iWork folks in your life (while I do use some of the iWork apps, I never rely on their file formats and always “save as” to something more interoperable).

I came across a stupid cool and useful project that fills a major gap in file format usability. WorkKit (GH) lets us crack open Apple’s iWork documents (i.e., Pages, Numbers, and Keynote files) and actually read what’s inside them. The whole thing started with someone reverse engineering how these files work. Be warned: the rabbit hole goes pretty deep.

Back in 2013, Apple made this quiet but fairly massive change to how iWork stores documents. They switched from XML to Google’s Protocol Buffers, which is this binary format that’s way more efficient but also way more opaque. If you’ve ever wondered why you can’t just unzip a Pages document and read it like a text file anymore, that’s why.

The clever bit about how Andrew Sampson figured this out is that Apple actually leaves breadcrumbs in their own executables. The message descriptors for these Protocol Buffers are sitting right there in the binaries, and you can find them by scanning for patterns like .proto filename suffixes. Once you’ve got those, you can use SwiftProtobuf’s visitor API to reconstruct the actual schema definitions and see what Apple’s doing under the hood.

But Protocol Buffers alone aren’t enough to explain iWork’s architecture. Apple built this whole object-oriented layer on top of it, complete with inheritance hierarchies using super fields. They’ve got this runtime registry called TSPRegistry that maps type identifiers to Swift classes, basically recreating the kind of reflection you’d get in Objective-C. It’s actually pretty elegant.

The documents themselves are packaged as either directory bundles or ZIP archives, and inside there’s this Index.zip file containing what they call IWA files. These are collections of compressed protobuf messages, but Apple uses their own custom Snappy compression that skips the CRC32 checksums. Each IWA chunk starts with an ArchiveInfo message that tells you what’s coming next—the type IDs and lengths of all the subsequent protobuf messages.

One of the more clever attributes about this format is how it handles updates. There’s a should_merge flag that lets you do incremental saves, so you only have to write out the parts of the document that actually changed. If you’ve ever noticed how fast iWork apps save even massive documents, that’s probably why.

When it comes to actual content, things get interesting. Take media files (i.e., audio, video, GIFs, even 3D models): they all use the same TSD_MovieArchive message type. They’re only distinguished by flags and file extensions, not separate types. Images go in TSD_ImageArchive messages and reference their actual data through IDs. And if you’ve got equations in your document, the LaTeX or MathML source is tucked away in extension fields of those image archives, though you can also pull it from PDF metadata.

Tables are where things get really complex (to be fair, they’re kind of complex in MS Word, too — I should know). They use this tiled storage system with 256×256 cell chunks to manage memory efficiently. The cell data itself is packed with headers and storage flags that tell you which optional fields are present—things like Decimal128 values, Doubles, String IDs. Even borders are optimized, stored as stroke layers that define continuous runs instead of specifying borders for every single cell.

Shapes are defined by these PathSource enums that can be points, scalars, Bezier curves, callouts, and more. Each type stores its geometry differently, and Bezier paths just store sequences of path elements. Charts combine data grids with axes that have both style and non-style archives for properties like min and max values, plus series styling that lets you mix different chart types in the same visualization.

The whole style system works through inheritance chains. Everything that can be styled — paragraphs, characters, cells, shapes — uses this chain where properties resolve by walking from root to leaf. It’s a clever way to keep styling consistent while still allowing overrides where you need them.

WorkKit wraps all this complexity behind an IWorkDocumentVisitor protocol that just walks through document elements in order and gives you callbacks for paragraphs, tables, images, or whatever. By the time you see them, all the styles and transformations are already resolved and applied.

The format itself is shared across all three iWork apps, but each one structures its content differently. Pages has its body storage architecture; Keynote is slide-based; and Numbers is sheet-based. Same foundation, different houses built on top.

What’s somewhat remarkable is that someone sat down and figured all this out just by poking around in binaries and following the breadcrumbs Apple left behind. No security vulnerabilities or anything dramatic, just a really thorough understanding of how a major piece of software actually works under the hood.

The post has scads more details and is worth your time to digest. The code behind it is also all ready to be used, and I do hope this means we have a forward path to make iWork documents usable in the future (without having to boot a then-legacy OS into a VM just to get files in a usable format).

Normalizing Catastrophe

There’s something that truly bothers me every single day, due — in part — to what I do for a living (observe the consequences of failing to produce quality software at scale). At some point we have all just collectively decided that software being terrible is…fine! Normal, even. Remember when a calculator app leaking 32 GB of RAM would have been a scandal? Now it’s just Tuesday. We shrug, reboot, and move on with our lives.

So, you’re thinking this is an “AI” rant post (or, perhaps, the post I’m profiling was an anti-“AI” post). The thing is, this situation we’re in isn’t really about “AI,” even though “AI” is 100% making everything worse. The quality collapse was already happening. Is your VS Code eating all your RAM? MS Teams freezing your laptop? Chrome tabs multiplying like rabbits and consuming everything in sight? These problems have been around for years, and nobody seems to care enough to fix them.

We’ve just normalized catastrophic software failures.

What “AI” did was take all that existing incompetence and give it a megaphone. Now you’ve got coding assistants spitting out security vulnerabilities at scale, and companies like Replit accidentally wiping databases because “AI”-generated code went rogue. It’s not that “AI” created bad engineering practices; it just made it way easier to produce way more bad code way faster.

Here’s the unfortunate part, though: companies are replacing junior developers with “AI.” That sounds efficient until you realize that junior developers are how you get senior developers (oops?). Those entry-level positions where people learn by debugging terrible code and correcting their mistakes? That’s the pipeline. Cut that off, and in five years you’re going to have a massive shortage of engineers who actually know how to solve hard problems.

Meanwhile, the software we use every day keeps getting worse. Windows updates break things that were working fine. macOS Spotlight decides to write terabytes of data to your disk for no reason. iOS apps crash constantly. These aren’t edge cases or rare bugs; they’re just how things work now.

And the really frustrating thing? Big tech companies know about all this. Their solution? Spend billions on more data centers and infrastructure instead of fixing the actual software. Eventually you run out of power to run all those data centers, which is literally happening right now.

The abstraction layers keep piling up, each one adding overhead and complexity, and nobody wants to admit that maybe we’ve gone too far. Could it be we don’t need seventeen frameworks to build a simple web app. Perhaps efficiency should matter again.

The article argues we need to get back to basics: make quality matter more than shipping fast, actually measure how many resources your code uses, and promote engineers who write efficient code instead of just those who ship features. Stop treating software engineering like it’s just about moving fast and breaking things, because we’ve broken enough things already.

It’s not a technical problem at this point; it’s a cultural one. We forgot that good engineering means building things that work well, not just things that work well enough. And until we remember that, we’re just going to keep watching software get worse while pretending everything is fine.

This post hit home, since I cut my teeth on writing code for resource-constrained environments. While no one should engage in premature optimization, spending quality time on the design-side thinking about the eventual need for optimization is time well spent.

I’d further suggest subscribing to Denis’s “From The Trenches” newsletter. He definitely leans into “telling it like it is” vs. “what you want to hear”.

AstroDither

Two long “spinach” sections mean this last one will be both quick and fit for dessert.

AstroDither is a creative coding project by Robert Borghesi where visuals react to audio using some seriously spiffy web graphics tech. Borghesi saw a GIF online and thought, “I want to make that,” which kicked off this whole experiment with TSL (Three.js Shading Language) and WebGPU, the still-relatively-new graphics API that’s replacing WebGL.

There is way more going on under the hood than you’d think. Robert built a custom dither effect that only affects the 3D model so it can blend naturally with the rest of the scene, plus a fluid simulation coded from scratch that runs in a single pass for better performance. On top of that, there’s post-processing with more dithering and displacement effects, selective bloom that glows without using traditional masks (just clever workarounds), and chromatic aberration for that color-split look.

It is super cool just seeing someone having fun exploring new tech and solving interesting visual problems.

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

☮️

Leave a comment