Readability; Prying JSON From A Model’s Cold Deceased Inference; Proprietary Blurriness

A very mixed bag, today, as it’s been a pretty hectic week at work (we’re officially releasing our GreyNoise MCP server, today!).

Again, hopefully at least one section catches your fancy.

TL;DR

(This is an LLM/GPT-generated summary of today’s Drop using Qwen/Qwen3-8B-MLX-8bit with /no_think via MLX, a custom prompt, and a Zed custom task.)

- Readability: Explore various readability formulas and tools to enhance writing clarity and accessibility (https://wooorm.com/readability/)

- Prying JSON From A Model’s Cold Deceased Inference: Learn about structured output techniques to guide LLMs in generating well-formed JSON (https://nishtahir.com/how-llm-structured-decoding-works/)

- Proprietary Blurriness: Understand Apple’s private CSS property for Liquid Glass effects and its implications on web development (https://alastair.is/apple-has-a-private-css-property-to-add-liquid-glass-effects-to-web-content/)

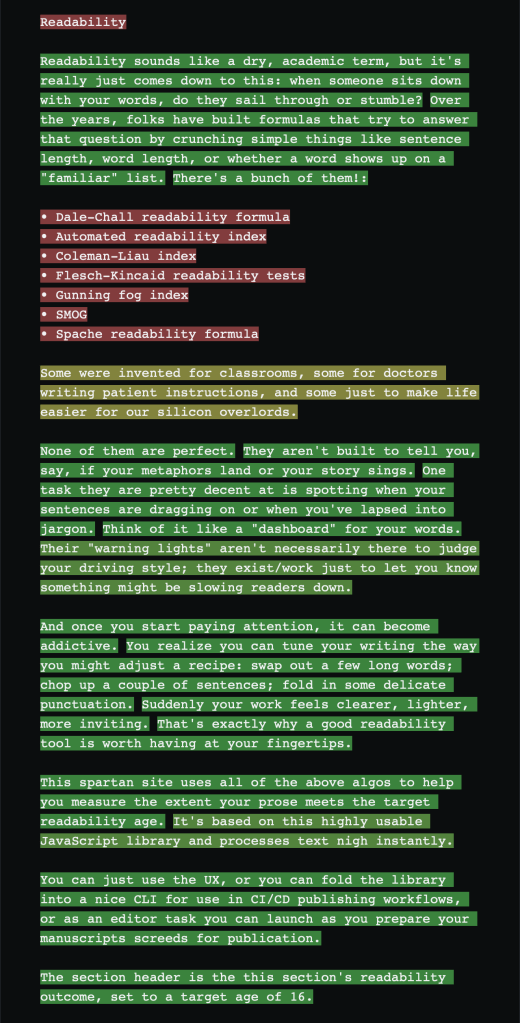

Readability

Readability sounds like a dry, academic term, but it really just comes down to this: when someone sits down with your words, do they sail through or stumble? Over the years, folks have built formulas that try to answer that question by crunching simple things like sentence length, word length, or whether a word shows up on a “familiar” list. There’s a bunch of them!:

- Dale–Chall readability formula

- Automated readability index

- Coleman–Liau index

- Flesch–Kincaid readability tests

- Gunning fog index

- SMOG

- Spache readability formula

Some were invented for classrooms, some for doctors writing patient instructions, and some just to make life easier for our silicon overlords.

None of them are perfect. They aren’t built to tell you, say, if your metaphors land or your story sings. One task they are pretty decent at is spotting when your sentences are dragging on or when you’ve lapsed into jargon. Think of it like a “dashboard” for your words. Their “warning lights” aren’t necessarily there to judge your driving style; they exist/work just to let you know something might be slowing readers down.

And once you start paying attention, it can become addictive. You realize you can tune your writing the way you might adjust a recipe: swap out a few long words; chop up a couple of sentences; fold in some delicate punctuation. Suddenly your work feels clearer, lighter, more inviting. That’s precisely why a good readability tool is worth having at your fingertips.

This spartan site uses all of the above algos to help you measure the extent your prose meets the target readability age. It’s based on this highly usable JavaScript library and processes text nigh instantly.

You can just use the UX, or you can fold the library into a nice CLI for use in CI/CD publishing workflows, or as an editor task you can launch as you prepare your manuscripts and screeds for publication.

The section header is the this section’s readability outcome, set to a target age of 16.

Prying JSON From A Model’s Cold Deceased Inference

If you have the misfortune of “needing” to work with LLMs, you likely have experienced what nigh every developer who’s ever begged an one of these stochastic parroters to “just give me [REDACTED] JSON” has: instead of, say, { "result" : [ "a", "well-formed", "array" ]}, you get { kinda, sorta, almost }. The machines are supposed to be smart, yet they act like toddlers with finger paint when faced with curly braces.

That’s why, in many online systems (remember, you’re interacting with a complex application, not merely a single model), “structured output” mode exists. To extend the automobile metaphor in the first setction, these are the “seatbelts” that keeps your model from swerving into nonsense. Instead of praying to the prompt gods, you hand the model a schema and say, “Color inside the lines, please.”

If you’ve ever wanted to understand how this magic actually works (spoiler: it’s less vibes, more mathy token-wrangling), this piece — “How LLM Structured Decoding works’ — is a fantastic deep(-ish) dive into what magicks you may need to incant to achieve the desired resuls (well, most of the time, anyway).

Proprietary Blurriness

Borrowing part of the lede from the second section: if have had the misfortune of not heeding my warnings on social media to avoid *OS 26 like we should have avoided the plague, then you are stuck (with me!) in the land of blur.

If you are presently on an *OS device and using either Safari or Safari Technology Preview (I always recommend using the latter to avoid some of the drive-by web attacks aimed at the former), or Apple apps that have “WebKit” views, then you will start to experience the blurriness in web contexts as well as in the apps.

Apple quietly added a private CSS property (-apple-visual-effect) that lets apps styled with webviews mimic the new “Liquid Glass” design language in *OS 26. On, er, paper, it may look clever. Developers could just drop in a CSS rule and get the same frosted-glass effect Apple uses in native UI.

The catch?

It’s locked behind private APIs, meaning third-party developers can’t ship it without App Store rejection, and it won’t work on websites you host. In practice, this makes it a toy for Apple’s own teams rather than a real web capability.

I can hear your “So, what?” all the way up here in Maine.

The “so what” is that it highlights Apple’s ongoing two-tier system: polished (yes, I’m being unusually kind) UI integration tricks for themselves and scraps for everyone else.

While thiss blog’s author treats this as fun trivia, it’s really a reminder of how Apple leverages private hooks to make its own webviews seamless while leaving outsiders stuck with the stigma of clunky in-app browsers.

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

☮️

Leave a comment