The Hidden Art Shaping Interactive Worlds; Go Fonts

Just two for this Tuesday (so, Typography Twosday?), and no TL;DR, given the long form nature of the first section.

The Hidden Art Shaping Interactive Worlds

Over the past few weeks, two distinct but related events sent me down a much-needed rabbit hole to the universe of video game fonts that brought at least a few hours respite from the burgeoning dystopian nightmare that is 2025.

The first was the discovery of “In Other Waters” — a recent-ish-ly released video game where you guide a stranded xenobiologist through a mysterious alien ocean as an AI companion. Explore a non-violent sci-fi world of wonder and fear, uncovering the history and ecology of an impossible planet. It was a super cheap Steam grab and has been fun to casually (more like randomly) dip into to keep the mind occupied. The overall ambient experience in the game is soothing, and it’s pretty clear Gareth Damian Martin (the game’s creator) knows a thing or three about typography and how to use it in a video game context for everything from control interfaces to narrative display.

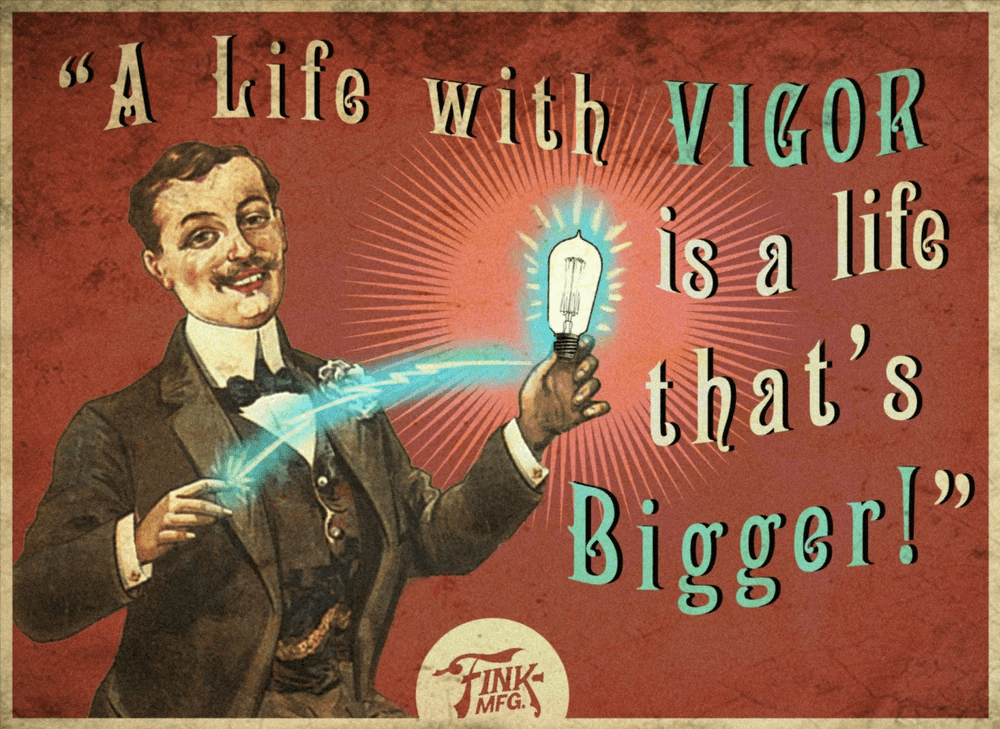

The second was randomly coming across The BioShock Wiki Fonts page, which lists the typefaces used across the BioShock series. It shows how fonts like Futura, ITC Anna, Plaza, and many (many) more fonts contribute to the Art Deco, Art Nouveau, and other aesthetics of Rapture, Columbia, and more. Each section on the page highlights where these fonts appear in-game and visually catalogs their role in shaping the games’ visual style.

Typography might not be the first thing folks think about when they pick up a controller, but it quietly shapes how we experience entire virtual worlds. Unlike print or web design, type in games lives under unusual constraints: it has to render in real time, across wildly different devices, while keeping players immersed for hours on end. What started as a necessity (tiny pixel grids squeezed onto arcade screens) has become a full-blown design discipline. Today, a single font can become a cultural icon, earn millions in licensing revenue, and even carry the identity of a game franchise. Yet the business models, technical hurdles, and cultural stakes of gaming typography remain uniquely complex.

In game engines, typefaces aren’t simply dropped in like they are on a website. They’re rebuilt to fit the physics of real-time rendering. Unity’s TextMesh Pro relies on Signed Distance Fields (SDF) and Multi-Channel SDFs. Both are clever “tricks” that store shapes as gradients instead of pixels, letting fonts scale without becoming a blurry mess or grinding frame rates to a stop.

The technical demands climb higher in Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR). In VR, every frame has to be drawn twice (once per eye) at a frenetic 90 frames per second (FPS), while text remains legible whether it’s floating in peripheral vision or locked to a heads-up display (HUD). AR adds even more chaos! Type has to hold up against whatever unpredictable background the camera sees, often requiring minimum font sizes, high contrast ratios, and real-time background analysis just to stay readable.

Mobile glowing gaming rectangles bring their own headaches, with compression formats, bandwidth caps, and heat management all pressuring design choices. Developers have learned that even small tricks like smart batching or runtime font generation can slash memory use and boost frame rates in ways that keep text performant without sacrificing quality.

If rendering is a technical headache, licensing is a financial migraine. Traditional font licenses, as we’ve noted in a few Drops, are cheap for print or desktop use. They may set you back anywhere from ten bucks to a few hundred. But, if you do read the fine print, most fonts explicitly forbid embedding them in games. Developers typically have to buy “Application” or “Video Game” licenses that start around ~$400 USD and scale quickly. Foundries take these terms pretty seriously, too. Indie publisher Stonemaier Games once received a $60K USD licensing bill that only dropped to $8K after negotiation. Some foundries have adapted to the reality of interactive media, offering more reasonable license terms, but the font industry still truly hasn’t fully caught up to gaming’s needs.

Fonts in games aren’t just functional. If/when a game reaches a certain popularity/success threshold, the typography in it can evolve into meatspace cultural signals. For example, Minecraft’s chunky block type mirrors the very geometry of its world and is instantly recognizable far outside the game, on merch, memes, and fan sites. Rockstar’s use of Pricedown in Grand Theft Auto turned the single word “WASTED” into a meme with autonomous life, endlessly remixed on the socials.

Different genres have developed their own typographic codes: fantasy titles lean on classical serifs that echo manuscripts, horror prefers distressed letterforms that seem decayed before the player even encounters monsters, and sci-fi universes reach for sleek sans-serifs with neon edges that whisper futurism. Localization complicates things further. Translating often isn’t enough to ensure a given game “works” in another language. Right-to-left (RTL) scripts or character-dense languages like Chinese often require entire redesigns to preserve usability and atmosphere. The Witcher series has shown how careful typographic adaptation can make a game feel native in dozens of languages.

The history of gaming typography is itself a story of ingenuity. Early arcade designers crafted literal miracles within 8×8 pixel grids, producing character sets that were both elegant and legible under severe constraints. Monotype’s Toshi Omagari has described this era as an “outsider typography movement,” where necessity birthed a new art form. As graphics evolved, typography moved from purely functional to atmospheric, part of the world-building toolkit. Bethesda’s Fallout 4 integrates the same font across in-game UIs, promotional materials, and merchandise, baking type into the franchise’s DNA. At the cutting edge, new tools are reshaping the field: AI generators like AIfont can spin up typefaces on demand, while variable fonts allow a single file to morph seamlessly across weights and widths, perfect for games that need to adapt across multiple platforms without ballooning in size.

Accessibility, once an afterthought, has become a standard. Modern games routinely include font size sliders, color options, and alternative typefaces, often guided by frameworks like Microsoft’s Xbox Accessibility Guidelines. Research backs up these changes: sans-serifs tend to be easier for visually impaired players, proper contrast ratios improve legibility for everyone, and small tweaks like differentiating easily confused characters or setting comfortable line spacing can dramatically reduce eye strain. What began as niche advocacy has become simply good design, benefitting everyone.

Looking ahead, typography in games is set to become even more dynamic. Fonts may soon adapt in real time to player mood, behavior, or narrative context. Designers are already experimenting with deliberately glitchy anti-aesthetics, nostalgic pixel revivals, and handwritten authenticity as a counterpoint to slick AI-generated sameness. In VR and AR, eye-tracking could allow fonts to shift based on where you’re looking, and experimental research is pushing toward haptic typography that delivers tactile feedback in virtual worlds. With gaming already outpacing music and film combined, and with metaverse-scale experiences on the horizon, typography is becoming a technical, cultural, and emotional backbone of the industry.

The fonts we see on our glowing rectangles aren’t just mere labels. They’re tools of immersion, carriers of meaning, and every so often the single most recognizable piece of a game’s identity. Over the next decade (yes, that is an unusual bit of optimism from me regarding humanity’s longevity), type will not only deliver information but increasingly become part of the play itself.

Go Fonts

TIL (OK, in reality, around two weeks ago) Golang has its own Go font.

The Go team needed something better than the usual suspects for displaying code and UI text. Off-the-shelf fonts like Courier or Arial either looked clunky on screens or made it too easy to confuse characters like 0 (zero) and O.

Instead of settling, they worked with Bigelow & Holmes to design a family of fonts that are clean, legible, and open source. The thinking was that if Go is about clarity and simplicity in code, its fonts should reflect those same values.

They also wanted to give developers something they could actually use without worrying about licenses or readability quirks. That’s why Go Sans has a humanist style—more natural and readable than Helvetica’s cold (and boring) geometry. It’s also why Go Mono has slab serifs for “sturdiness” without losing legibility.

Both families follow legibility standards, scale well on screens, and don’t break layouts because they’re metrically close to fonts we already use.

“Practical, approachable, and built to make the work easier” describes both the fonts and Go’s foundational philosophy.

The section header shows the markdown source for this section set in Go Mono.

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

☮️

Leave a comment