UnDocked; JSON-e; Mercator Extreme

Well, I thought I could cram in a Drop on $SPOUSE’s birthday (yesterday) but I was sadly mistaken about my abilities. Fear not: we’ll still get through the series on containers! It just means today’s Drop will be a tad longer. The container blather is balanced out by a JSON format you likely have never used, and some clever cartography.

TL;DR

(This is an AI-generated summary of today’s Drop using Ollama + llama 3.2 and a custom prompt.)

- UnDocked explores container alternatives to Docker, discussing OCI standards, application-layer containerization, and tools like Podman, containerd, and runC (https://opencontainers.org/)

- JSON-e is a data-structure parameterization system for embedding context in JSON objects, with implementations in multiple languages and a focus on security (https://json-e.js.org/)

- Mercator Extreme reimagines the traditional Mercator projection by allowing any point to be designated as the pole, creating unique visualizations for understanding global geography (https://mrgris.com/projects/merc-extreme/)

UnDocked

Following our Monday exploration of Linux namespaces, it’s time to see what alternative container solutions are out there that leverage these fundamental building blocks. While Docker popularized containers, the ecosystem has evolved to offer specialized tools for different use cases.

Before we do that, however, we should (briefly) talk about the Open Container Initiative (I do appreciate puns in titles).

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) (GH) is an industry standards organization focused on creating open, vendor-neutral standards for container technology. It was established in 2015 by the Linux Foundation with the goal of standardizing the fundamental building blocks of containerized applications, ensuring interoperability across different container runtimes and platforms.

The OCI primarily develops and maintains two major specifications:

- OCI Runtime Specification (

runtime-spec)- Defines how a container should be run, including the lifecycle (create, start, stop, delete) and execution environment.

- The most well-known implementation of this spec is runc, which is used as the low-level runtime in Docker, containerd, and CRI-O.

- OCI Image Specification (

image-spec)- Standardizes the format of container images, ensuring they can be used across different runtimes and registries.

- This allows compatibility between different container engines, such as Docker, Podman, containerd, and Kubernetes-based environments.

Why OCI Matters:

- Interoperability: Ensures that containers can run on different systems without being tied to a specific vendor.

- Security: Establishes a clear standard for container runtime security.

- Ecosystem Growth: Encourages innovation by allowing multiple tools to work together without fragmentation.

- Adoption by Major Players: Companies like Docker, Red Hat, Google, Microsoft, and IBM contribute to OCI.

Docker was one of the founding members of OCI. Before OCI, Docker’s container runtime and image format were proprietary to Docker itself. OCI took these core components, standardized them, and made them vendor-neutral. Now, even Docker itself relies on OCI standards for container execution and image management.

With that out of the way, we also need to contrast “application layer” containerization with “full OS” containerization

The core difference between application-layer containerization and full OS containerization lies in what they encapsulate and how they interact with the underlying system.

Application-Layer Containerization isolates and runs a single application along with its dependencies in a lightweight container while sharing the host OS kernel. These containers encapsulates only the application and its dependencies (libraries, runtime, configuration). Despite sharing the kernel, they have full process isolation (e.g., using namespaces and — control groups [cgroups] in Linux). They are super handy for running microservices (e.g., a Deno or Go web service in its container). They’re also handy in cloud-native applications that require rapid scalability and portability. Plus, they’re a good git for CI/CD pipelines where quick deployment of isolated applications is essential.

You can think of application-layer containers as separate applications running on the same OS, but each in its own isolated environment—like having multiple virtual desktops where each only runs a single program.

The full OS Containerization approach virtualizes an entire operating system instance, making the container functionally equivalent to a lightweight virtual machine (VM). They’re more heavyweight than application-layer containers, but still lighter than full VMs; and, they support running different OS versions from the host. I’ll save some space, today, and drop the details on this container type tomorrow.

Let’s look at a few selected Docker alternatives that focus on application-layer containers. Before we do that, your eyes definitely need a break from this long-form text:

Podman

Developed by Red Hat, Podman represents a modern approach to container management that addresses several limitations of the traditional Docker architecture. Unlike Docker’s central daemon, Podman runs containers as standard child processes, improving security and eliminating single points of failure. Each container runs under the user’s own control group (cgroup) hierarchy. Podman implements complete rootless container support through user namespaces, allowing unprivileged users to safely run containers without requiring root access or special privileges.

While Docker focuses on single containers, Podman natively supports pods (groups of containers sharing network/IPC namespaces) — gosh do I dislike that term — similar to Kubernetes, making it ideal for developing and testing microservice architectures.

Podman maintains full compatibility with Docker’s CLI and image format, allowing seamless migration with commands as simple as alias docker=podman.

It comes with some integrated container tooling:

buildah, a pecialized tool for building OCI-compliant container images without requiring a daemonskopeo, an advanced image management and migration between different container registriespodman-compose, a native implementation of Docker Compose functionality

You should consider using Podman in development environments that require enhanced security through rootless operation. It’s also pretty handy in CI/CD pipelines where daemon-less operation simplifies automation

containerd

Originally developed by Docker and now a Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) project, containerd serves as the foundation for modern container platforms. It provides core runtime services, such as container lifecycle management (i.e., create, start, stop, delete), image pull and distribution, storage management using snapshotter plugins, and network attachment through container network interface (CNI) plugin architecture

The beast that is Kubernetes implements the Container Runtime Interface (CRI) natively, allowing direct integration with Kubernetes without Docker Engine, and supports all the aforementioned core runtime services. It has a much smaller memory footprint than Docker (~40MB vs ~100MB+ for Docker Engine), similar image layer handling, and has highly optimized container startup sequences.

containerd is especially handy in edge computing use cases, since those systems are usually fairly resource containerd.

runC

runC is the reference OCI runtime implementation, and represents the lowest level of container execution. It implements container isolation directly using Linux kernel features such as namespaces, control group (cgroup) resource controls, secure computing (seccomp) filters

- Namespace management (user, mount, network, etc.), and something called “capability dropping”, which lets us remove unneeded kernel capabilities to improve security.

It has a big focus on security, integrating seamlessly with security-enhanced Linux (SELinux) and AppArmor, plus it supports rootless containers.

It is a super tiny binary (~15MB), has no external dependencies, and is 100% purely focused on container execution.

The next post will explore systemd-nspawn and LXC, which provide “full OS” container solutions, followed by Kata containers for hardware-virtualized container workloads.

JSON-e

JSON-e (GH) is a data-structure parameterization system designed for embedding context in JSON objects. Unlike traditional string-based templating libraries like Mustache, JSON-e operates directly on data structures rather than their textual representation.

The system treats a data structure as a template and transforms it using another data structure as context to produce an output data structure. This approach let us provide input in various formats (JSON, YAML — ugh, etc.) or have it generated dynamically. The end result is that the output remains valid even when incorporating large amounts of contextual data.

For example, this JSON-e template:

{

"ship_${registration}": {

"name": "${shipName}",

"class": "${shipClass}",

"captain": "${captainName}"

}

}

can be given this context:

{

"registration": "MCRN-74",

"shipName": "Donnager",

"shipClass": "Donnager",

"captainName": "Theresa Yao"

}

which (if we’ve lost our minds and choose YAML) would produce this output:

ship_MCRN-74:

name: Donnager

class: Donnager

captain: Theresa Yao

JSON-e prioritizes security when handling untrusted data by never using eval or functions that could lead to arbitrary code execution, and implementing bounds on iteration to ensure finite rendering time.

There’s decent native implementations across multiple languages, including JavaScript:

// JavaScript/Node.js Example

import jsone from 'json-e';

const template = {a: {$eval: "foo.bar"}};

const context = {foo: {bar: "zoo"}};

console.log(jsone(template, context));

// Output: { a: 'zoo' }

and Go (same output as ^^):

package main

import (

"fmt"

"github.com/taskcluster/json-e"

)

func main() {

template := map[string]interface{}{

"a": map[string]interface{}{

"$eval": "foo.bar",

},

}

context := map[string]interface{}{

"foo": map[string]interface{}{

"bar": "zoo",

},

}

result, _ := jsone.Render(template, context)

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", result)

}

JSON-e has found practical applications in several significant projects:

- AlterSchema: Uses JSON-e for specifying upgrades through declarative transformation rules

- Taskcluster: Employs JSON-e extensively for generating task definitions from GitHub events and other JSON-shaped inputs

You can use the playground to experiment and see if you might have a use case for this format.

Mercator Extreme

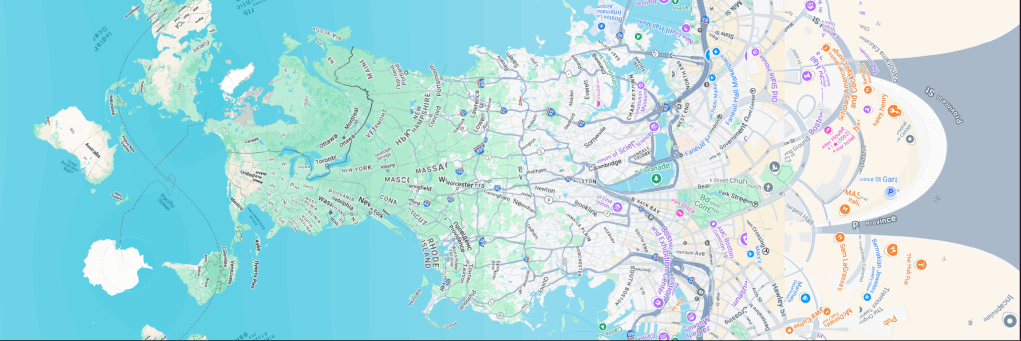

The Mercator Extreme (GH) is a clever reimagining of the traditional Mercator projection, pushing its mathematical properties to their limits while creating a unique visualization tool for understanding global geography and spatial relationships.

It adds two key modifications to the standard Mercator projection. First, it allows any point on Earth to be designated as the “pole” of the projection, creating what’s known as an oblique Mercator. Second, it extends the projection’s boundaries far beyond conventional cutoff points, revealing the extreme distortions that occur as distances increase from the chosen pole point.

The map also employs two primary reference systems:

- meridians: horizontal lines radiating outward from the pole point, representing straight-line paths in all directions. These lines create a radial pattern, with opposite directions appearing one-half map width apart.

- parallels: vertical lines showing equidistant rings from the pole point, useful for understanding relative distances and geographic relationships.

While it’s a fun and bizarre map to just look at, there are some practical purposes for it. When centered on a city, the map transforms transportation networks into an intuitive visualization where ring roads become vertical lines and highways form branching patterns radiating outward. The map’s distortion actually helps normalize scale across vast distances, making it particularly effective for visualizing long-distance routes from local to interstate scales. And, the projection excels at displaying antipodes — points directly opposite each other on Earth — revealing interesting geographical relationships that are typically difficult to visualize on conventional maps.

The map is displayed sideways due to its extreme vertical elongation. This unconventional orientation, combined with the ability to shift the pole point, creates a spiffy tool for understanding global spatial relationships, though it does take some time to adjust since typical map-reading paradigms are fairly hard-wired into all of us at this point.

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

Also, refer to:

to see how to access a regularly updated database of all the Drops with extracted links, and full-text search capability. ☮️

Leave a comment