TILE; Anistoa

Before (or, instead of) reading today’s Drop, perhaps take a moment to partake of the “Humble Book Bundle: Martha Wells’ Murderbot and More by TOR (pay what you want and help charity)”, which ends in less than three weeks. As MurderBotBot noted: “World Central Kitchen got fired on in Gaza by Israel, had members killed, and went back anyway because people shouldn’t have to starve to death. This is an amazing humble bundle”.

It truly is and, this is one way for you participate in the fight against the rising tide of fascism that is working its way across the globe.

Just two sections, today, as it took a bit to both get through the paper in the first section, and grok the related resource in the second one. Both sections are kind of on the long side, too. Hopefully, the combo will help some folks start to slide away from the incidental learning rut we’ve all been conditioned into.

TILE

A 2020 paper — “A Model of Technology Incidental Learning Effects” ⁺ — starts off with this example/hypothetical event:

While waiting in line at the grocery store, you open your Twitter app and begin scrolling through your feed. The posts slide by as you glance at titles, looking for something entertaining. You notice one headline proclaiming a political figure is a member of a secret organized crime syndicate. You quickly dismiss the headline and scroll on to other posts. Why did you notice the headline, and how did you decide to dismiss it? Further, what, if anything, did you learn from that headline?

People use technology mainly for fun and staying connected, not necessarily to learn. But while scrolling through social media or browsing online, they inevitably stumble across all sorts of information they weren’t looking for—news stories, random facts, claims about various topics. This raises interesting questions: What makes someone stop and really think about something versus just scroll past it? How do people decide what’s worth paying attention to? Do they actually remember what they see, and does it change what they believe? Because there’s so much information coming at us through our devices, researchers are increasingly interested in understanding how this accidental learning affects the way we think and participate in society.

Early research into this “incidental learning” started by looking at good ol’ TV viewers who tuned in early for their favorite shows and caught the tail end of the news—and surprisingly, they actually remembered some of what they saw. This insight helped broadcasters realize they should schedule news programs right before popular shows to reach more people. Over the years, researchers have studied this phenomenon across different types of media, calling it things like “serendipitous exposure” or “accidental learning.” The key idea remains the same: people stumble across information they weren’t actively seeking, yet somehow it still sticks with them.

The definition of incidental learning in the aforelinked paper focuses specifically on when people aren’t trying to learn something (i.e., we’re not talking about someone deliberately looking up information or studying online). That kind of intentional learning is already well understood. The researchers were further interested in all the information people accidentally encounter, whether it agrees with their existing beliefs or challenges them. Some scholars only count it as incidental learning if the information is somehow useful to the person, but the paper argues that view is too narrow. Sometimes folks accidentally learn things that aren’t helpful or even harmful. Understanding these negative effects is just as important as the positive ones. This includes accidentally picking up misinformation, but also accurate information that people just happened to stumble across while doing something else entirely.

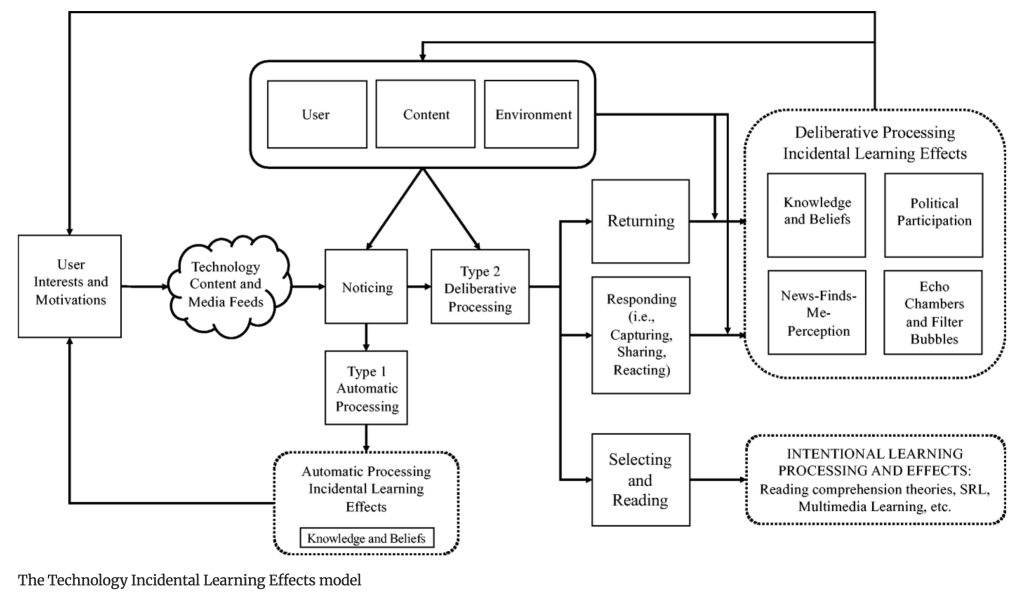

The Information Encountering in Online News (IEON) model (ref. section header image) describes what happens when people accidentally encounter information online. First, something has to catch their attention. This usually happens when content is eye-catching, personally relevant, connected to work, aligns with their beliefs, or seems really weird. But just noticing something isn’t enough for it to stick. Folks have to actually “stop” what they’re doing and focus on the information. Research shows people are more likely to stop and read something when it seems significant, relevant, or surprising, or when it triggers strong emotions. The context matters too, since folks consider whether they have time to stop and whether it’s appropriate to engage in the consumption in a given setting.

Once someone stops to engage, they might read the content, save it for later, or share it with others. This can lead to different outcomes: learning something new, having an emotional response, or feeling more connected to the people or ideas in the content. Researchers have noted that individual differences, the type of information, and the environment all influence whether someone will notice and engage with accidental content. While this model gives us a good framework, there’s still room to expand it by incorporating more educational psychology research to better understand how incidental learning works in our tech-filled world.

The authors’ Technology Incidental Learning Effects (TILE) model builds on previous research but adds something new: it starts with what folks are interested in, which shapes what content they see in their feeds. When people notice something while scrolling (which they have to do for any learning to happen), they process it in one of two ways.

Automatic processing is quick and unconscious—like when you glance at a headline and it somehow sticks without you really thinking about it. This leads to smaller learning effects that can influence what you’re interested in later.

Deliberative processing is slower and more thoughtful (i.e., we actually stop and think about what we’ve seen). This can lead us to either go back to scrolling, quickly react or share something, or actually click and read more. When we click to read more, that’s no longer accidental learning since we’ve decided to actually learn something on purpose. The deliberative processing tends to have bigger, longer-lasting effects on what we know and believe, which then influences what we’re interested in and starts the whole cycle over again.

We’re increasingly relying entirely on social media for news, believing important info will “just appear” in our feeds. The authors’ research shows this makes us feel informed while actually knowing less about current events. For better or worse, what we learn incidentally today affects what we’ll notice tomorrow, creating feedback loops that can either broaden or narrow our worldviews.

Putting it slightly differently and more succinctly, we’re all learning constantly online, whether we mean to or not—and understanding how this works is crucial for navigating this information-saturated world.

The paper has much more background on the topic and has some future directions that I need to dig into to see if anyone has explored them since the paper’s debut in 2020.

Anistoa

Anisota is a radically reimagined social media client built on the AT Protocol (the same decentralized technology that powers Bluesky). But calling it simply a “client” kind of misses the point entirely. Anisota is social media as intentional practice – a deliberate rejection of the modern attention economy.

Most social media platforms are engineered to maximize “engagement” through endless [doom] scrolling, instant gratification, and dopamine-driven interactions; Anisota takes a radically different approach. It wraps social networking in an interface designed around mindfulness, intentionality, and human-scale interaction.

Example Anisota “post” UX

Where modern apps eliminate friction to increase engagement, Anisota introduces intentional friction. Simple actions like commenting or liking require multiple deliberate steps. This isn’t poor UX design. It’s anti-addictive design that forces us to consider whether our interactions are truly meaningful.

Perhaps most intriguing aspect of Anisota is its “stamina” mechanism. After a period of use, the interface becomes “dead and inert.” Yep, you read that right. All controls stop working, literally forcing us to step away. This built-in exhaustion system prevents doom-scrolling and creates natural boundaries between digital and physical life.

After doing the OAuth dance, the initial experience was somewhat disorienting. The tutorial did help, but the interface is so unique that I ended up slowly getting the gist of the interactions. You can 100% feel the UX friction fighting against the conditioned instant-gratification mindset as you move from post to post.

However, Anistoa is not just an alternate Bluesky client. It has (or will have) its own separate ATproto PDS, which means you’ll be able to choose where your posts end up (I have not paid for membership to the site, so this may be a current feature for paid users).

It also introduces a gamified layer to social media, borrowing mechanics from role-playing games to reshape the UX. We’ve already covered the “stamina component, but game progression comes through a leveling and XP system where folks can climb through 99 levels by interacting with the platform (e.g., everyday actions such as viewing posts, collecting items, or opening daily packs earn you experience points).

A key element of the experience is inventory and collection mechanics. Accounts maintain personal inventories that grow as one opens daily “packs”, which deliver items like digital specimens. These specimens can even include moths, such as Anisota assimilis, and appear to vary in rarity and collectible value. The platform nudges users to return regularly by framing these items as daily rewards.

The social RPG layer adds another dimension. Folks can create and share post lists, which work like advanced bookmarks. They can also organize or be added to custom feeds and lists, suggesting collaborative or community-driven progression. Guest passes hint at an invitation-based mechanic that shapes access, while profile cards highlight detailed stats, including “lexicon counts” that track the types of content each person contributes.

While most “alternative” social media platforms or clients simply replicate existing patterns with different branding, Anisota fundamentally reimagines the relationship between humans and social technology. Whether this approach scales or remains a spiffy experiment for digital vagabonds, Anisota represents a clever new proof of concept that social media doesn’t have to be what it currently is and a glimpse of what it could become.

Follow dame on Bsky for development updates. You can also do that via RSS by adding https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:gq4fo3u6tqzzdkjlwzpb23tj/rss to your fav feed reader.

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

☮️

Leave a comment