hl; hk; MPD

Y’all do not want to know how many taglines I come across that make the immediate claim that XYZ tool/tech/service is “fast and powerful,” but you’ll get a glimpse today of a few. Two are recent additions to this “bold [bald-faced?] claims” club, but the last one comes from a much simpler time.

TL;DR

(This is an LLM/GPT-generated summary of today’s Drop. This week, I continue to play with Ollama’s “cloud” models for fun and for $WORK (free tier, so far) and gave gpt-oss:120b-cloud a go with the Zed task. Even with shunting context to the cloud and back, the response was almost instantaneous. They claim not to keep logs, context, or answers, but I need to dig into that a bit more.)

- The

hlcommand‑line tool quickly formats JSON, logfmt or plain‑text logs, offering powerful filtering, sorting and paging features for fast log exploration (https://github.com/pamburus/hl). hkis a Rust‑based high‑performance Git hook manager that runs linters and formatters in parallel with read/write locking to avoid race conditions, simplifying reliable pre‑commit workflows (https://hk.jdx.dev/).- Music Player Daemon (MPD) runs as a lightweight background service that serves a SQLite music library over a simple text protocol, enabling multiple clients to control playback simultaneously and scriptable, low‑resource audio management (https://www.musicpd.org/).

hl

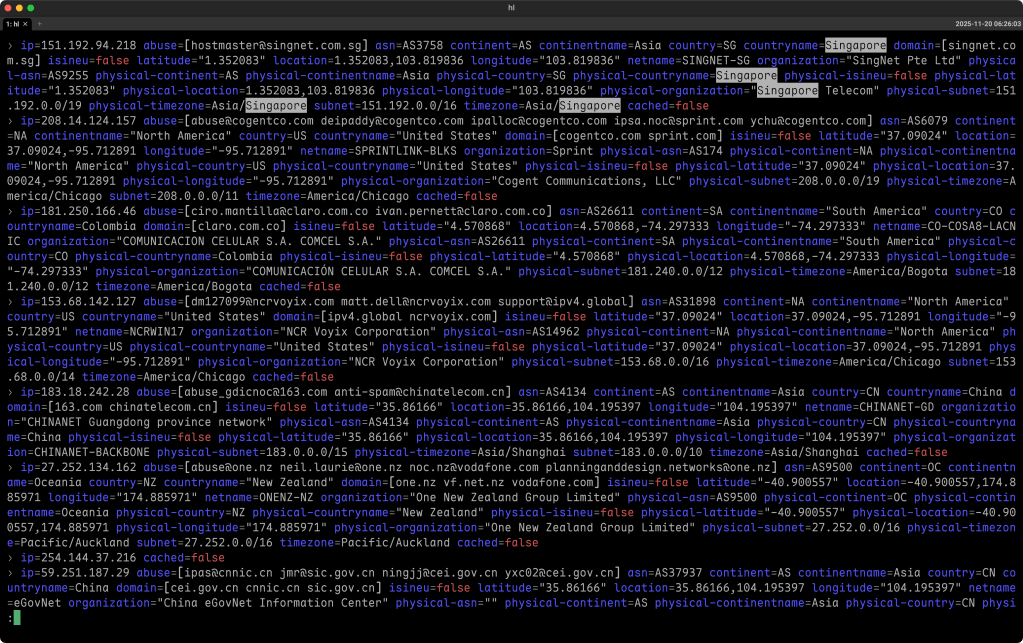

The hl project is a command‑line tool that turns raw log files—whether they’re in JSON, logfmt, or simple text—into something you can actually read without wading through dump after dump of machine output. It’s built for speed, so even a multi‑gigaboot (I’m in Canada this week, so the pronunciation thing is rubbing off on me) file can be parsed in a couple of seconds on modern hardware, which makes it handy for developers, ops engineers, or anyone who needs to troubleshoot quickly.

When you run hl on one or more log files, it automatically pipes the result through a pager (usually less), so you can scroll through the formatted output the same way you would with any long text stream. If you prefer to handle paging yourself or you’re feeding hl live data, you can turn paging off with a simple flag. The tool also supports a streaming mode that lets you watch logs as they grow, which is useful for following the output of a service in real time.

Filtering is one of the strongest points. You can limit the view to a certain log level (e.g., error, warning, info, etc.) by specifying a level option. You can also narrow results by time, using natural language phrases like “today”, “yesterday”, or relative offsets such as “‑3h”. The tool understands a range of timestamp formats, and you can tell it to display times in UTC, your local zone, or any other timezone you name.

If you need more precise control, hl lets you filter on arbitrary fields. You write a key‑value condition, ask for substring matches, or even apply regular expressions. Complex queries are possible too: you can combine several criteria with logical operators, test for the presence or absence of fields, and use set membership checks. The query language is expressive enough for most real‑world log analysis without having to write a script.

Sorting is another built‑in feature. With a flag, you can ask hl to read many files and output the messages chronologically, even if the original files were written out of order. In “live mode,” it can merge streams from many sources, keep them sorted within a short time window, and keep the display up‑to‑date as new lines appear.

Installation is straightforward on the major platforms. On macOS you can use Homebrew, and on Linux you can download a prebuilt tarball, install from a package manager like Pacman, or compile with Cargo if you prefer Rust tooling. Windows folks should switch operating systems but can get it via Scoop, and there are also instructions for NixOS and for running the binary directly from a URL. All of those methods give you the same binary, so the usage is identical no matter how you obtain it.

The tool is highly configurable. It looks for configuration files in standard system‑wide and user locations, and you can override any setting with environment variables or command‑line arguments. This includes things like the default time format, which colors to use, whether empty fields should be hidden, and which pager to invoke. Themes let you switch the color scheme on the fly, and you can create custom themes by providing a small (ugh) YAML or (yay!) TOML file that describes foreground, background, and text modes for different log elements and levels.

Because hl relies on an external pager, make sure you have a working version of less installed (or override the default). On Windows the native build of less can be problematic, so the recommended approach is to install it from Scoop or Chocolatey, which provides a version that respects ANSI escape codes correctly.

In practice you might start with a simple command like “hl myapp.log” to see a nicely formatted view. If you only care about errors, you’d add “‑l e”. To watch a live log, you could pipe “tail -f” into hl and turn paging off with “‑P”.

To, say, find everything that happened yesterday in the “auth” component, you’d combine the time filter and a field filter: “hl *.log --since yesterday --filter component=auth”. And if you want to export the raw, unmodified lines after filtering, you can ask for raw output so you can pipe the result into another tool or save it.

Overall, hl gives you a fast, flexible, and human‑friendly way to explore logs without having to learn a full‑blown log management platform. It works well in the terminal, integrates cleanly with existing Unix pipelines, and its rich filtering and sorting capabilities let you get to the insight you need with just a few keystrokes.

So, I guess this one is truly both “fast” and “powerful”!

The section header is an example of me looking for Singapore IPs in some Geolocus output.

hk

When you first start a project, you’re probably thinking about the big stuff: the language you’ll use, the architecture, maybe a CI pipeline. The last thing you want to hear about from the likes of folks such as me is “Don’t use GitHub for your remote.” That must come across like we’re being pedantic. But the reality is that a solid Git workflow, with good hooks and an SSH‑based remote you control, can save you hours of frustration long before you ever push a pull request.

That’s where hk (GH) (a.k.a., “High‑Performance Git Hook Manager”) comes in. It’s a tool built in Rust by Jeff Dickey, the same person behind the super cool mise, and it’s geared toward folks who want their Git hooks to run fast and reliably. Instead of trying to be a one‑size‑fits‑all solution, hk focuses on doing one thing well: executing linters and formatters in parallel while avoiding the dreaded race conditions that can corrupt files.

The secret sauce is a read/write file‑locking system. When a tool only checks code (for example, eslint in “check” mode), it grabs a read lock, which means any number of read‑only tools can work on the same file at the same time. When a tool actually writes changes (like prettier or black with the “--fix” flag), it takes a write lock, and hk makes sure only one writer touches a given file at a time. The result is that you can run a whole suite of checks in parallel without worrying that two formatters will try to rewrite the same file simultaneously.

To configure hk you write a small hk.pkl file. The language it uses – Pkl – is a programmable configuration format that lets you validate schemas, import other configs, and even write tiny functions (the link goes to a previous Drop where we covered Pkl). Here’s a minimal example that sets up eslint and prettier for a JavaScript project:

amends "package://github.com/jdx/hk/.../Config.pkl"

import "package://github.com/jdx/hk/.../Builtins.pkl"

local linters = new Mapping<String, Step> {

["eslint"] {

glob = List("*.js", "*.ts")

check = "eslint {{files}}"

fix = "eslint --fix {{files}}"

}

["prettier"] = Builtins.prettier

}

hooks {

["pre-commit"] {

fix = true

steps = linters

}

}

That file says, “When a commit is about to happen, run both ESLint and Prettier on any staged JavaScript or TypeScript files. If a check fails, automatically run the fixer.” Because eslint is declared as a read‑only check, it can run in parallel with other read‑only steps, while prettier’s fix operation will acquire a write lock only when it actually needs to rewrite a file.

hk also leans on mise for tool management. Instead of reinventing version pinning, hk simply calls mise use to make sure the exact version of eslint or prettier you want is available. If you need a more complex workflow, you can define a mise task and reference it from hk. The command‑line interface is straightforward:

hk install # installs the hooks into .git/hooks/

hk run pre-commit # runs the pre‑commit hook manually

hk check --all # lint the entire repository, useful for CI

Because hk stashes any unstaged changes before it starts, runs the linters, stages any files it modifies, and then restores the stash, you never lose work in the middle of a commit. The whole process is designed to be invisible to you while still being fast enough that you don’t feel a delay every time you type git commit.

If you’re already using a self‑hosted Git server accessed over SSH (which, by the way, is a great way to keep your code away from the pitfalls of megacorps owned by billionaires), hk fits right in. You control the remote, you control the hooks, and you get the performance boost of Rust without any heavy Node.js dependencies. It’s a tidy, low‑maintenance setup that scales well from a single repo to a monorepo with dozens of packages.

Give it a try on a small project, watch the pre‑commit hook finish in a flash, and you’ll see why a self‑hosted SSH remote plus a well‑behaved hook manager can feel a lot less daft than relying on a generic cloud service from day one.

(This one seems to also have earned the “fast and powerful” moniker.)

MPD

This last one harkens back to a time just before humanity decided to jump, headfirst, into the abyss.

Back in 2016, there was a post about how to set up a full “fast & powerful” stack to replace iTunes (for the kids, that was the predecessor to Apple Music, which is now just “Music” and is an even worse app than iTunes was). We’re just going to focus on one of the tools, today — Music Player Daemon (MPD) — as it is still being maintained and works well (we’ll cover clients in a future Drop).

Imagine you could keep your music playing regardless of where you are, regardless of what window you have open, and still be able to control it from a terminal, a web page, or a tiny phone app. While you could lean on proprietary solutions like Apple’s speaker pods or expensive kit from Sonos, you 100% do not have to, since that’s precisely what MPD does. Instead of being a monolithic player that tries to do everything, MPD is a small background service that only knows how to play audio files. It listens on port 6600, builds an SQLite database of your library, and handles all the playback details.

Because the user interface is completely separate, the moment you close the client, the music keeps going. You can have several clients connected at the same time – a terminal program on your laptop, a GUI on your desktop, and a mobile app on your phone – all talking to the same daemon without ever interrupting the stream. The design is the classic Unix approach: one thing well, and everything else built around it.

You’ll find the architecture easy to picture. Your music folder feeds into the MPD daemon, which stores metadata in a tiny SQLite file. Clients reach the daemon through a simple text‑based protocol. The daemon then sends audio to the output device of your choice. Because the protocol is just plain text, you can script anything with a few lines of shell, Go, Deno, or whatever language you prefer.

On macOS, getting MPD up and running is as easy as a single Homebrew command:

brew install mpd mpc

A minimal configuration file in ~/.mpdconf looks like this:

music_directory "~/Music"

db_file "~/.mpd/database"

state_file "~/.mpd/state"

port "6600"

auto_update "yes"

audio_output {

type "osx"

name "Mac Audio"

mixer_type "software"

}

Save the file, start the daemon, and MPD will scan the folder, create the database, and be ready to accept connections.

Once the server is running, you need a client, which you can hit the above link for or wait for a future Drop (perhaps even tomorrow’s Drop!). But, just so you can get going today, the command‑line tool mpc (which the brew command, above installed) lets you control playback from any shell script.

The real advantage shows up when you start treating playback as data. Since MPD keeps a live SQLite database, you can run raw SQL queries against it, pull the current playlist into DuckDB for analysis, or write a script that changes the music based on external events. For example, a security researcher could have a script that plays a calm track when network traffic is low and switches to an alert tone when a threat detection system reports high severity (so, in reality, it’s always playing an alert tone). All of that is just a TCP connection away.

Performance is another strong point. Searching a library of fifty thousand tracks feels instantaneous because the daemon does the heavy lifting in native C++ and never has to load a UI to respond. The memory footprint stays in the single‑digit megabytes, even on a Raspberry Pi, which means you can run MPD on a headless server and control it from anywhere on your LAN.

There are a few trade‑offs to keep in mind. You’ll need to become comfortable editing a plain‑text configuration file, and the default clients have a utilitarian look that may feel dated compared with modern polished apps. MPD also doesn’t provide built‑in iOS syncing; you’d still need a separate tool if you want that capability.

Overall, MPD embodies the same philosophy you use when building data‑driven network tools: keep the core service simple, expose a clean protocol, and let other programs do the heavy lifting. Install the daemon, point it at your collection, pick a client that fits your workflow, and you’ll quickly wonder why you ever settled for a bloated all‑in‑one player.

Fast & powerful, indeed!

FIN

Remember, you can follow and interact with the full text of The Daily Drop’s free posts on:

- 🐘 Mastodon via

@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev@dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev - 🦋 Bluesky via

https://bsky.app/profile/dailydrop.hrbrmstr.dev.web.brid.gy

☮️

Leave a comment